The first portion of this article examined our tendency to “spiritualize” our theological language. This can happen when taking words that were first given dynamic metaphorical use for articulating something of our experience with God, and calcifying their meaning such that the only interpretation considered is one that stays entirely in “the spiritual realm,” without anchor in this material world. Those who find that trend unhelpful might consider this a danger of what I called the spirituality perspective on reality. In contrast, what I will call the realist perspective views all of creation as one, integrated reality where our spiritual, psychological, and social worlds are emergent from and dependent upon our biological world as surely as chemistry emerges from and is dependent upon physics.

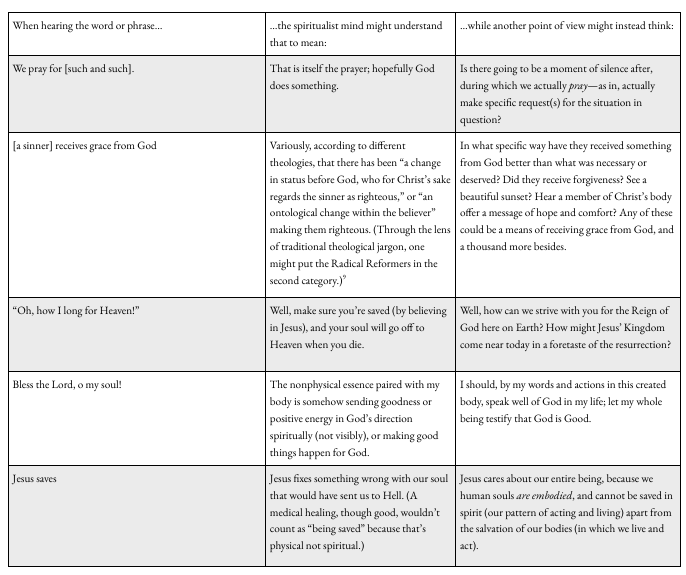

A full articulation of that latter perspective is certainly more conceptually complex than what the Radical Reformers would have preferred, but the realist articulation of anthropology would lend itself well to the project of working backward from fully spiritualized words (divorced from their original anchor) to hear again what they might have spoken as metaphorical or dynamic use of plain language. This is part of what this article, in both halves, contends: there is great potential in carrying on the Radical Reformers’ project of returning to the roots of Christianity not just in church structure or practices but the language of our faith. Taking a realist perspective, understanding all creation to be one reality, not divided into two disparate realms, all our words for things of creation should refer to realities we can observe. Consider a few possibilities, drawn even from common parlance rather than academic theology:

These are only a few examples; readers may think of many more. But there are at least two areas in which voices of the Radical Reformation, doing theology in plain language, sharply criticized theology that has allowed accretions of tradition to “spiritualize” the words of scripture and faith. Regarding both baptism and communion, early Anabaptists clearly placed great value in their practices while denying the theological claims of Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed neighbors. I am reminded, however, that there are Friends among our readers whose faith has set aside the outward expression of even those practices, and some discussion of their articulation of simplicity in faith is warranted.

While I have much to learn about early Quaker history, several thoughts could be included from George Fox and the First Publishers who “unceremoniously discarded most of the rituals, institutions and theologies developed in 1600 years of Christian history.”2 First of all, in common with the Radical Reformers, their denial of the established church’s theological claims “did not mean that Friends were without affirmations. Their emphasis was on putting into action these statements which they were willing on occasion to call ‘professions’ or ‘confessions’ of faith.”3 Building on the understanding that “the plain and simple life is one centered around and directed by the Light and its leadings,” practices of simplicity for early Quakers (including plain dress, plain speech, refusing oaths, and refusing to produce or trade certain goods) were individual practices that set Friends apart from society as a recognizable community, drew direct lines from faith to practice, and by casting an alternative to ills of the broader society, “stood as Friends’ witness and judgment against the world for its injustices and oppressions.”4 And to focus specifically on language, while the practice of plain speech is often first explained in terms refraining from flattery or flowery titles, analysis of “broadsides” texts (a form of flier used as cheap public communication) from a wide number of early Friends shows that even with individual authors’ distinctives, the Quaker writers as a whole were set apart from non-Quakers of the same period by their “clearly personal and direct” style, using “I/thou” or “I/you” language significantly more frequently than other broadsides, with the resulting impression being that of greater directness, urgency, or passion in the argument or exhortation being made.5 This alternative pursuit of simplicity offers a spiritualist alternative on baptism and communion, distinct from the early Anabaptists’ realist understanding, though both sharply contrast with the magisterial churches’ theological understanding.

The magisterial churches practiced infant baptism in accordance with the belief that baptism coincided with the individual’s salvation. Going back as far as Augustine, the spiritualist point of view separated the activity of the “physical realm” (involving water, clergy, and body of the baptizand) and the activity of the “spiritual realm” (God bestowing forgiveness, entry of the soul into the Church universal) and concluded that since the truly important matters were the “spiritual” ones, the holiness of the clergy person was irrelevant. With infant baptism, the (undeveloped) belief or participation of those being baptized was likewise deemed irrelevant. Having designated and separated physical and spiritual dimensions into separate realms, eventually all that was essential was not subject to observation.

The Quaker route to simplifying the practice as a restoration seeking to undo the accretions of tradition would be to simply observe spiritual baptism: since the observable actions with water are not what actually accomplishes the spiritual transformation, they could be considered unnecessary at best.

In contrast, baptism among the early Anabaptists was centered realistically on things that were very much observable: the faith commitment expressed by the confessing individual seeking baptism, the community of faith receiving and accepting a new member, and the symbolic significance of the actions of the baptism itself. The transformation thus effected is grounded in these realities—and in a realist view, they are thus observable and spiritual. Consider the words of Balthasar Hubmaier:

In receiving water baptism, the baptizand confesses publicly that he has yielded himself to live henceforth according to the rule of Christ. In the power of this confession he has submitted himself to the sisters, the brethren, and the church, so that now they have the authority to admonish him if he errs, to discipline, to ban, and to readmit him…. Whence comes this authority if not from the baptismal vow?6

Opponents of Anabaptism reading such a passage might not have recognized the theological work in this at all; if they are seeking significance primarily in “spiritualized” vocabulary, Hubmaier has not mentioned God’s activity directly or invoked anything ontologically of the “spiritual realm.” However, implicit in such an articulation of baptism is the belief that God, in Christ, receives our faith personally and relationally as it is offered in public confession–with Christ’s presence and participation not just assumed by virtue of divine omnipresence, but also seen through Christ’s body, the Church, in ways that are observable.

Perhaps with nearly as stark a contrast as in baptism, the magisterial churches’ accounts of communion (or Eucharist, or the Lord’s Supper) are in strong contrast with the early Anabaptist practice and understanding. Students of theology are often taught that broadly speaking, there are three understandings of communion: Transubstantiation, the Catholic view, holds that the elements are ontologically or spiritually transformed into the literal body and blood of Christ and are no longer bread and wine, though they maintain their external appearances as such. Consubstantiation, the Reformers’ alternative, teaches that while the elements remain bread and wine, the real essence of Christ’s body and blood are present “in, with, and under” the elements such that they could be said to have a dual nature. And thirdly, there are others who hold a “merely symbolic” understanding of communion, understanding the Lord’s Supper as an act of commemoration but without any invocation of spiritual or ontological transformations in the elements themselves. (The Quaker articulation of spiritual communion, with Christ and with other believers, again upholds a spiritualist take that what is truly important does not depend on any physical elements of bread or cup, and considers them unnecessary for accomplishing the spiritual communion sought.)

Laid out in such terms, the “merely symbolic” view is defined nearly as much by what it is perceived to be denying or lacking as what it actually communicates. This contributes to misunderstanding the Radical Reformers’ theology of communion. As some early sixteenth century Anabaptist martyrs were questioned about communion, their responses express defiant denial: “I know nothing of your baked God.”7 Thus, even a scholar focused on Radical Reformation spirituality was able to note that the early Anabaptist’s communion “was not a shallow casual observance but rather a vivid reenactment of Jesus’ last meal” claims that this is “[d]espite the minimalist theology implied in these [martyrs’] testimonies.”8 Minimalist theology? Those martyrs were not expressing their own theologies; they were actively denouncing theologies of transubstantiation or consubstantiation, using powerful plain speech as they did so.

The most useful positive claims about communion for this context might come in Meno Simon’s description of communion as the “Christian marriage feast” where “Jesus Christ is present with his grace, Spirit, and promise.”9 With Christ and community gathered, the story of Jesus’ passion and the words shared over these elements do change them–but not by invoking some ontologically inaccessible transformation. In the same way that I cannot treat my wedding ring the same way that I could treat a band of precious metal–though it once was only that, before it became involved in personal, subjective history and the context of covenant vows before a community of faith–the elements of communion become the bearers of an emergent spiritual reality that is truly dependent on the beliefs, commitments, and understanding of the gathered faith community and Christ’s presence among them. Still bread and cup, they are no longer “just” bread and cup; their involvement in our covenant community has a real impact on how we treat them and how they affect us. If this is to be categorized as a “symbolic” understanding, then so be it; the realist perspective recognizes that it is the symbolism that is active at the spiritual level of reality, governing our actions and carrying spiritual import. (Remember, for the realist that the word “spiritual” is not an invocation of some inaccessible realm of ontology, but a recognition of emergent complexity, where the spiritual takes precedence over the material reality it depends on as much as my wedding ring is real and takes precedence over the band of precious metal.) In the words that my tradition uses in the celebration of communion, the bread which we break is the communion of the body of Christ; that latter spiritual reality is emergent from and dependent on both the bread and the shared faith of the community.

There may be many words of our theology that would benefit from reconsideration. The Radical Reformers’ interest in scraping away all the accretions of tradition so that the faith of the early church could be heard anew can be applied not just to the trappings of church buildings and institutions, but to the words with which we do theology, and in some cases the way we hear the words of Scripture themselves. Too often, our words have been “spiritualized” such that many folks no longer expect to observe something like “God’s grace,” or even to imagine that those words might refer to physical actions in this world God has made. The Spirit may be invisible, like the wind, but we should no more expect folks to believe in a God whose actions cannot be felt or observed any more than in a strong wind that does not even rustle the leaves or move a single blade of grass. God alone transcends creation; let us speak as plainly as we can communicate our meaning, and let our words about God’s actions point to things we can observe in God’s one created universe. We will not be any less theological for being grounded in the reality of this good physical world.

Caleb is a graduate of Eastern University and Bethany Theological Seminary, and thankful for many professors and mentors in his background in sociology and theology. He serves part-time alongside Irvin Heishman as a pastor at West Charleston Church of the Brethren, a multilingual/multicultural and open and affirming congregation north of Dayton, Ohio. Caleb is thankful for that rich community’s embrace of diversity as a family of faith in which to raise two children with his wife, Allie. When he’s not caring for his children or tied up with church activities, Caleb’s always eager to join in some tabletop games, theological conversation, or both together!

- Alvin J. Beachy, “Concept of Grace in the Radical Reformation,” The Mennonite Quarterly Review (36, no. 1: January 1962, accessed via ATLA), 91–92.

- Charles E Fager, “The Quaker Testimony of Simplicity,” Quaker Religious Thought (January 1972, accessed via ATLA), 14.

- Dean Freiday, “‘Atonement’ in Historical Perspective,” Quaker Religious Thought (January 1986, accessed via ATLA), 28.

- Fage, “Quaker Testimony of Simplicity,” 9-14.

- Judith Roads, “Early Quaker Broadsides Corpus: A Case Study” Quaker Studies (17/1, 2012, accessed via ATLA), 41.

- Quoted by Timothy George, “The Spirituality of the Radical Reformation,” 34.

- Quote of a martyr from West Friesland, in Timothy George, “The Spirituality of the Radical Reformation,” 36. Other lines cited include “What God would you give me? One that is perishable and sold for a farthing?” or the allegation that if the communion theology of those questioning were true, then the priest who had celebrated Mass that day had “crucified Christ anew.”

- ibid, 36.

- Quoted in the same, 36.